“Ahh, yhes, you have just missed him, he has gone to jail for shooting a man with a poisoned arrow.."

We had driven for over 1000 kilometers over the African Plains. . The previous three villages had all pointed us in the direction of this little village, saying the last guy who knew how to do the long distance running and persistence hunting would definitely be here.

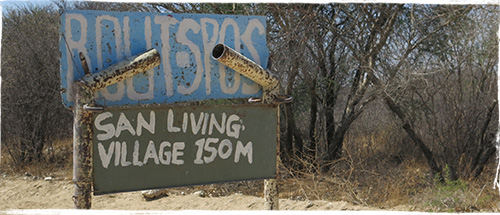

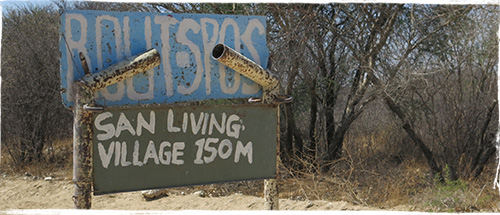

The previous evening, our guide Werner, known as "Honey Bird", had told us a history on the San (the Western term to categorise a multitude of bushmen tribes living all the way from Botswana to South Africa). The Ju/’hoansi, our hosts, are one such tribe, and call an area of 90,000 sq km around the Nyae-Nyae pans home.

Since they banned hunting in Botswana last year, the Naye-Naye conservancy area is the last place in Namibia where the Bushmen are still permitted to hunt using traditional techniques and we were here to find proof of the endurance running hypothesis:

Original humans hunted by running down and tracking prey over the hottest hours of the day. Humans have a unique ability to stay cool (sweat) with an efficient and elastic running style enabling us to out-last Antelope who can only manage short bursts to run away before they have to cool themselves down by breathing. Through clever tracking and consistent running, the humans are able to move the antelope on before they are fully recuperated and the beast ultimately keels over from heat exhaustion.

The drive from the village was a ponderous one, and we were becoming pessimistic about whether we would even get to meet someone that knew how to do the persistance hunting. Just as we were about to give up, a demure figure sitting across the room inquired,

“Are you guys doing a project?”

“We are looking for the last of the persistent hunters, but have hit a dead end.”

The mysterious figure was Aleksandra Orbeck Nielsen, who had left a glamorous career in Paris and New York to set up a conservation trust, called: Nano Fasa; to help protect the last wild zone of Namibia. Her goal was to set up a sustainable future for the people in the area. She knew the best hunters around and was about to launch, ‘The Barefoot Academy’ based around 5 branches:

The Hunter “Tracking is like dancing, I feel happy.”

The Gatherer “If we all share, we have enough.”

The Healer “Healing makes our hearts happy and our bodies strong as the antelope”

The Story Teller “We tell stories to teach, to prepare, to share and to connect.”

The Sustainer “When we heal the earth, we heal ourselves.”

The next morning Aleks was off to film a documentary, and we decided to go for a run with Ben McNutt’s bushman friend Toma. Ben had been working with Toma and his friend !Ao for the last ten years, leading expeditions to Namibia through his company Woodsmoke. As Toma glided effortlessly through the bush, we witnessed human movement at its most natural, he was deftly moving as humans have done in this part of Africa since before the dawn of humanity.

Back in the village, we met Toma's 80 years old father, squatting by his hut (while his son slouched on one of the chairs), who regaled us with tales of what he called ‘the running hunt’ and how they used to do it in this area.

“I wish my children would still do the running hunting”, said the old man. “They have become lazy and because they go to school have not had enough time to learn our traditional ways.”

Only 1 in 10 bow and arrow hunts are successful and the older villagers are frustrated that the young are too lazy to pursue this efficient and successful method of running hunting.

Schools, sitting in chairs and the introduction of secondhand first-world padded shoes are affectively crippling the Ju/'hoansi. As a result, running hunting, one of the most original methods of human pursuit is on the verge of dying out.

Ju/’hoansi like Toma and his brother have both gone to school, discovered chairs (they even have two chairs outside their hut) and started wearing poorly fitting secondhand Western shoes (often at least 2 sizes too big or too small). After being coerced by their insistent father, they have tried the running hunting, but so far without success.

“We gave up.”

“It was too hard.”

Toma and his brother say that they cough from smoking and as a result of tuberculosis. Although they reluctantly admit they ‘should’ stop smoking and start running to make their lungs stronger.

As the sun rose on our final day and we set off up the hills to Nhoma camp,, which had become rundown by an infamous Boer who had committed the crime of selling the Ju/’hoansi the free giveaway secondhand shoes he had received as ‘donations’ from the West.

Aleks has recently launched a tracking school and the skill of running hunting will be part of it. Students will come for a minimum of 2 weeks to help build up the camp, contribute to projects, and learn the ancient ways of these humble, wise and beautiful people.

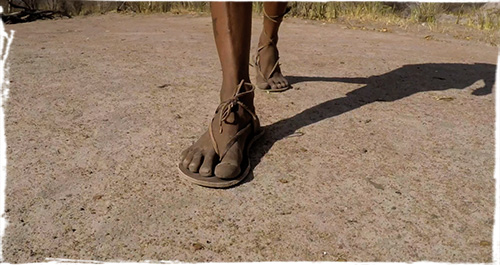

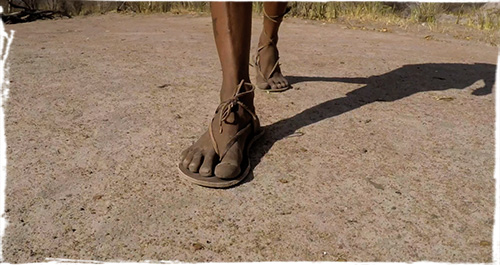

It was easy to distinguish the people that had started wearing Western shoes, as their toes were already warped. Whereas those who had stuck to the original natural sandals had beautiful straight toes. The people of Nhoma only hunted in the traditional bushman sandals – these days mainly made of tire rubber. The local cobbler complained of the lack of skins to make the shoes in the original way. They used to make two different types of sandals – one for hunting with a big toe groove for extra grip and a flat one for everyday use.

As the sun burnt into the bush, the film makers were capturing the locals gathering the larvae to make their poisonous arrow heads and we set off on our 1000km return trip back to Windhoek, on the way witnessing a final termite hatch at Roy’s camp. As a wise lady said, “Termites show that when we unite together we can build great things.”

We look forward to all coming back to inaugurate the tracking school, don the locally made bushmen sandals and run down a Kudu.. and try to escape without a poisoned arrow in our ass!

- Galahad Clark